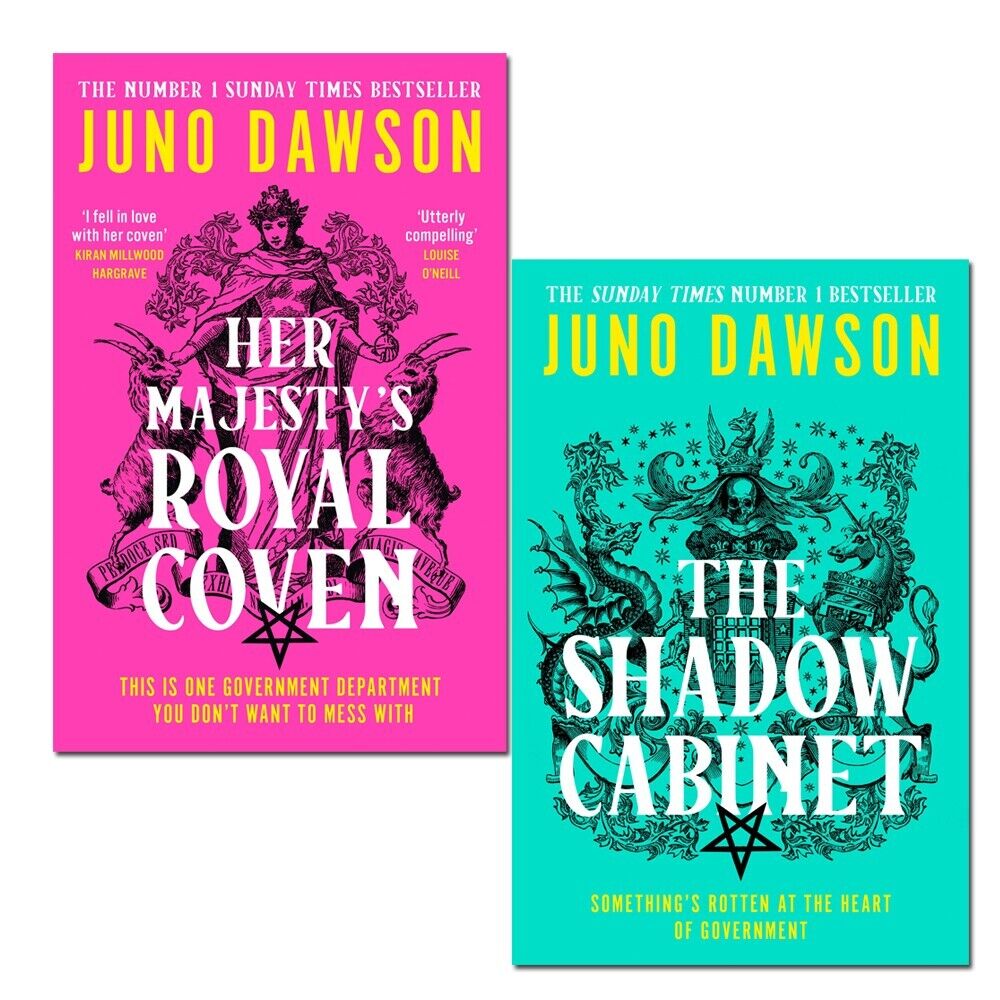

I was so looking foward to Juno Dawson’s Her Majesty’s Royal Coven. Modern witchcraft set in Hebden Bridge, which came highly recommended by both a friend whose taste I trust and the local bookstore that sold it to me? What could be better as escapist reading? In fact, I anticipated enjoying it so much that I bought the sequel before I even started the first volume and savoured my anticipation of losing myself in the West Yorkshire equivalent of Deborah Harkness’s All Souls series (recommened by another friend whose taste I trust and which I enjoy enormously).

So it is with great regret that I must inform you that Her Majesty’s Secret Coven is the lastest of my very rare ‘did not finishes’, and this was after I got over 150 pages in. Usually if I make it past page 50, I will keep going with a book, even if only out of pure bloody-mindedness. This, however, felt like too much of a slog. The characterisation was remarkably flat, particularly of the women who were portrayed as archetypes rather than indivuals. Given that this is a story predominantly about women, with a plot centring on female identity, this is a serious problem, one reinforced by a confusing plot with gaping holes in it. I spent most of the time struggling to understand what was happening or why characters were choosing to act in the ways described.

But the biggest disappointment was the aspect I had been anticipating most eagerly – the setting. As a Hebden Bridge resident, I freely admit to being an ‘offcumbden’. But the town and its surrounding villages have a unique enough personality for me to feel, even after only seven years of residence, that I know them at least a little bit. And they are definitely not the town depicted in this book. Yes, they form a small pocket of liberalism, not to say radicalism, enfolded by the Calder Valley in the more generally conservative rural West Yorkshire. And yes, the 1960s hippie vibe which is central to the town’s identity is being diluted by an influx of the professional middle classes (of which I freely admit to being one). Sitting halfway between Leeds and Manchester, even the vaguaries of Northern Rail cannot detract from the attraction of the town to commuters. But for all that, Hebden Bridge is still very much Happy Valley, not Nappy Valley. I don’t recall ever meeting a yummy mummy, as asserted in one description of a local café, and this is after five years of schoolgate attendance. Dawson appears to see Hebden Bridge as a version of Brighton in the north, which it is not. It is its own distinct place, with its own unique, often contradictory, always fascinating character, one which Dawson fails to capture.

The geography also doesn’t make sense. The book is full of descriptions of characters’ homes, but I was unable to locate any of them in my mental map of the area. The actual map that forms the frontispiece is no help, drawing as it does on the imagery of maps in fantasy novels. By the time I gave up, I found I was lost, not in the story but rather in confusion. I kept longing to find my way back tot he real world, rather than continue to make my way through a fantastical vision of the placy I call home, peopled by unreal phantasms, not people with recognisable conflicts and motivations. My recommendation is, if you want to discover the complex magic of Hebden Bridge through fiction, try the work of Sally Wainright rather than Juno Dawson. Happy Valley is on iPlayer and Riot Girls is due for broadcast this year. Or better yet, come visit, and experience this darkly enchanting place for yourself.