A Question of Identity

In my last post, I spent quite a lot of time thinking about the word ‘intimacy’ as use by Matt Houlbrook in Songs of Seven Dials, and how this use might apply to one of my own current projects. In this post, I want to focus on another word that Houlbrook uses, namely ‘cosmopolitan’, this time not in relation to anything I am currently writing, but rather in relation to a piece of historical work that I am still, largely, trying to avoid.

Houlbrook uses ‘cosmopolitan’ frequently to describe the population of Seven Dials. By applying it to this working-class neighbourhood in place of the perhaps more easily parsed ‘diverse’, Houlbrook highlights a central element of his argument about the racial makeup of the area as exemplified by one of his protagonists, Jim Kitten. Kitten, originally from Sierra Leone, was, as Houlbrook notes on a number of occasions, both Black and a British imperial subject. This duality appears to have been common among the denizens of the Kittens’ café, as well as some of the legal team who helped bring their libel case.

In demonstrating how Seven Dials was, however briefly, a ‘Black Colony’, in which interracial marriage and trans-imperial sociability were both accepted facts of daily life, Houlbrook offers an important corrective to the dominant image of Britain in general and London in particular in the 1920s and 1930s as white. Imperial migration in the period meant that any major city in Britain had its share of non-white residents seeking to make successful lives, including regular work, domestic security and the enjoyment of leisure. While the story Houlbrook tells is one of dreams thwarted by vested commercial interests, problematic local politics and a vituperative press, his depiction of the Kittens’ café points to the ways in which these aspirations were as important to the shaping of British society and culture in the first half of the twentieth century as the political rise of a self-made Yorkshireman like Bracewell Smith or the avant-garde experiments of the Cave club.

However, in the period that is Houlbrook’s focus, cosmopolitanism was about more than diversity of skin colour and class. It was also a term of disparagement, one with implicitly antisemitic overtones. It was used in popular culture to signify a rootlessness defined by the figure of ‘the Jew’, whose loyalty was deemed to lie with their co-religionists, rather than then nation. The Jewish capitalist with ‘no conscience and no fatherland’, [1] as evoked by John Buchan in The Thirty-Nine Steps, haunted the imagination of the 1920s and 1930s and shaped the politics of antisemites such as Sir William Joynson-Hicks, who served as Home Secretary from 1924 to 1929. Joynson-Hicks’ policies on migration were, as George Monbiot has recently pointed out, were designed to exclude Jewish refugees who, he believed, ‘put their Jewish or foreign nationality before their English nationality’.

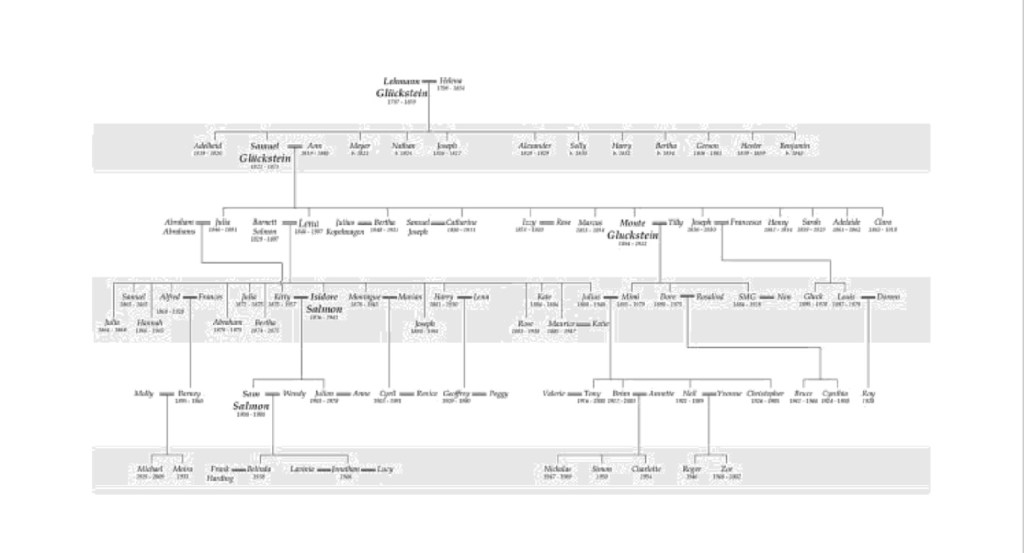

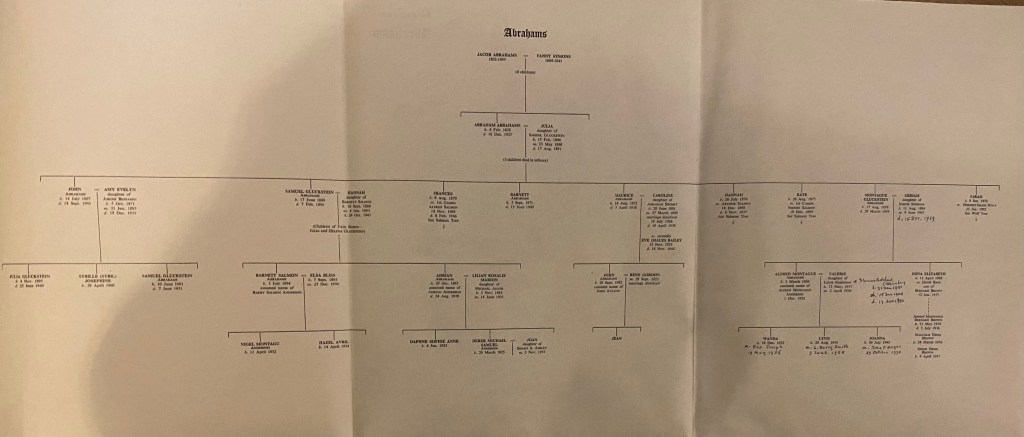

Which brings me, in a rather roundabout way, to the history of my own family. Because, like Monbiot, I am a descendant of Samuel and Anne Glückstein, whose son Monte and son-in-law Barnett Salmon, founded Lyons & Co. in 1887. And Jim Kitten worked, at least for a short period, at Cadby Hall, the four-hectare complex that formed the company’s headquarters in Hammersmith, where baked goods were made overnight to be shipped out in liveried trucks across the city. Houlbrook uses this association to set the Kittens’ café in counterpoint to Lyons Corner House, the most visible symbol of a firm that, in the first half of the twentieth century, ‘was woven into the fabric of British life’.[2] He describes Lyons’ teashops as ‘resolutely middlebrow’, ‘exemplify[ing] an increasingly demotic culture of dining out’ but still ‘underpinned by the unseen labour of a cosmopolitan workforce’. (20-21) All of which is undoubtedly true, but rather overlooks the history of Lyons’ itself as an business founded by those who might be considered members of that cosmopolitan workforce, not so very different from the ‘Italian, Belgian, Greek or Jewish entrepreneurs’ who set up shops and eating-houses in Seven Dials to provide for the area’s residence.(30) They were, after all, also migrants from overseas, looking to find stability and a better life in London. Lehmann Glückstein, Samuel’s father, was born in Jever in what is now north Germany; Samuel in Rheinberg, near the border with the Netherlands. The family arrived in London in 1843, via the Netherlands and Belgium, fleeing religious persecution, debt and accusations of fraud. Initially establishing themselves in Whitechapel, then ‘fast becoming a Jewish ghetto’ [3] and with a reputation for poverty and crime not unlike that of Seven Dials, it would be another half century before the first tea shop opened, on the back of a successful sweetshop and tobacconist business.

For me, these similarities between the Kittens and the Glücksteins raises complex and sometimes uncomfortable questions about how and why one family were able to succeed in their entrepreneurial efforts where the other ultimately failed. Because succeed the Glücksteins did, amassing business empire that, at its height, included the Strand Palace Hotel, the Trocadero and the Wimpy Bar chain, as well as the Lyons’ tea shops and food brand. Today the descendants of Lehmann and his wife Helena include chefs and television personalities, lawyers, bankers, journalists, artists, playwrights, doctors, entrepreneurs and at least two historians. The family’s success both derives from and reflects integration with British culture and identity, even as the many in the family held on to their Jewish faith. As Thomas Harding notes of descendants he spoke to when research his history of the family, ‘they all came across as confident, secure and possessing a profound sense of belonging.’ (my emphasis) [4].

Integration was important to the Glucksteins (as they became) because, unlike Jim Kitten, they arrived in Britain as migrants without claim to a British imperial identity. Samuel, the family’s vanguard, spoke no English and had no service to the British state in a world war to present as credentials for acceptance. Their claim to a sense of Britishness was far more fragile and needed to be constructed in large part through a corporate identity that deliberately adopted the name of its junior partner because it did not sound Jewish or German. Jim and Emily Kitten’s business, by comparison, appears to have been able to define itself as a meeting place for the Black community in Seven Dials because the Kittens felt able to lay claim to a British identity separate from their work, Jim through imperial subjecthood, Emily as a white native. Their decision to challenge John Bull in court over its characterisation of their café as a criminal hub suggests not simply an unwillingness but an outright refusal to mask their identity as a Black business for commercial ends.

At one level, it might seem simply a matter of racism that ensured the success of one and the failure of another. The Glucksteins could mask their origins and present as white Europeans in a way that Kitten could not. Yet antisemitic prejudice in Britain throughout this period was as vicious as anti-Black racism in this period. Comparing Lyons and Co. and the Kittens’ café brings to the fore the extent to which choices about whether to accommodate or resist prejudice played a role. Such choices, I would argue, were conditioned by the extent to which the Glucksteins and the Kittens felt themselves to be British. This in turn suggests that the barriers to success in the British imperial context of the early twentieth century were more complicated than simply a question of skin colour.

There is also question of timing and economics. There were more opportunities available to economic migrants in the nineteenth century than in the leaner years after the First World War, although the ease of movement of people increased in the later period. Whatever the reason for the different outcomes for the businesses, what struck me reading Songs of Seven Dials is the ways in which the Kittens’ café and Lyons are not simply examples of social hierarchy in London hospitality of the 1920s and ‘30s, but rather two sides of a coin. Both are stories of migrants using the sociability of hospitality to anchor themselves in the metropole. Both are stories of the negotiation of prejudice, not necessarily successfully. Above all, both are stories of what it meant to be British in the 19th and 20th centuries, who belonged, in what spaces and on what terms.

This last is, of course, a central question motivating Houlbrook’s work in Songs of Seven Dials. Bringing the Kittens’ café more directly into conversation with Lyons’ has the potential, I think, to push his arguments beyond the boundaries of the district, or even London, and to think more granularly about the definitions of the ‘Black Colony’ as part of a modern cosmopolitan culture. It also, of course, has the potential to speak, as Houlbrook suggests, to questions – about migration and belonging, sociability and identity – that are central to contemporary political debates.

I am still resisting getting drawn into more work relating to my family history, mainly because I already have too many projects on the go. But reading Songs of Seven Dials has given me all sorts of ideas about the social significance of that history and directions I might take any future research. In other words, it is a book that made me think and will, I predict, continue to do so for a long time to come.

[1] John Buchan, The Thirty-Nine Steps (Richmond, Surrey: Alma Classics, 2017; first published Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1915), p.10

[2] Thomas Harding, Legacy: One Family, a Cup of Tea, and the Company That Took on the World (London: William Heinemann, 2019), p.xxi.

[3] Harding, Legacy, p.25.

[4] Ibid., p.471.