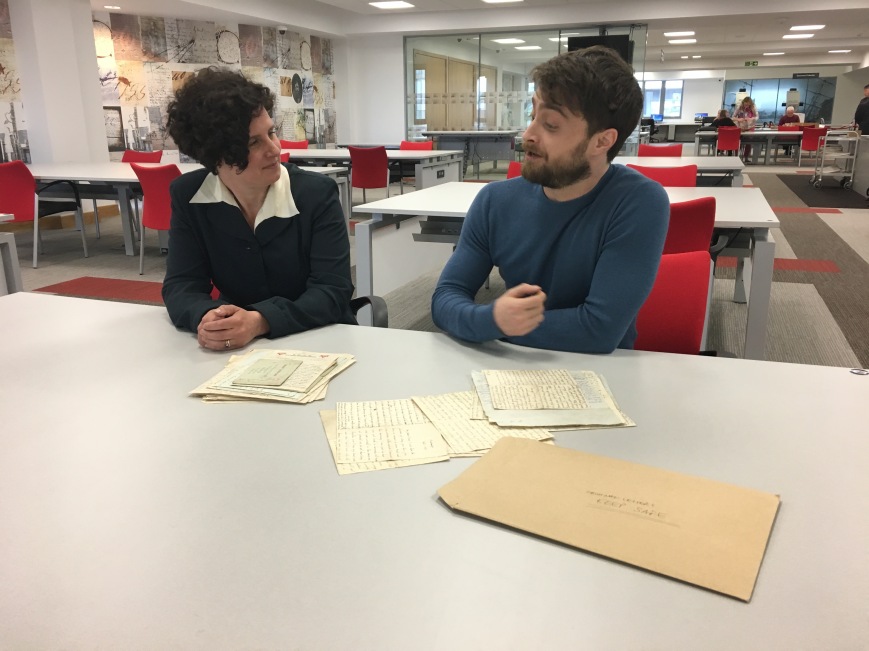

I was on television last night. If you follow me on Twitter, then you will probably have seen this already. Given that I was speaking to Daniel Radcliffe for Who Do You Think You Are?, both I and my department were quite keen to publicise this event. Since the broadcast, there has been quite a lot more interest, and some very interesting discussions about historical research for factual television, letters from women to soldiers during the First World War, and the significance of the Commonwealth War Graves cemetery at Dud Corner. In other words, this bit of academic public engagement, me bringing my historical expertise to bear on a popular subject in a very public forum, went as well as I could have hoped when my meeting with Dan was filmed back in May.

I was on television last night. If you follow me on Twitter, then you will probably have seen this already. Given that I was speaking to Daniel Radcliffe for Who Do You Think You Are?, both I and my department were quite keen to publicise this event. Since the broadcast, there has been quite a lot more interest, and some very interesting discussions about historical research for factual television, letters from women to soldiers during the First World War, and the significance of the Commonwealth War Graves cemetery at Dud Corner. In other words, this bit of academic public engagement, me bringing my historical expertise to bear on a popular subject in a very public forum, went as well as I could have hoped when my meeting with Dan was filmed back in May.

What has made this experience slightly ironic, however, is the coincidence of the publication of an article in The Economist late last week. Entitled ‘The study of history is in decline in Britain’, it argues that historians (by which the author, ‘Bagehot’, means academic historians) ‘increasingly devote themselves to subjects other than great matters of state: the history of the marginal rather than the powerful, the poor rather than the rich, everyday life rather than Parliament. These fashions were a valuable corrective to an old-school history that focused almost exclusively on the deeds of white men, particularly politicians. But they have gone too far. … What were once lively new ideas have degenerated into tired orthodoxies, while vital areas of the past, such as constitutional and military affairs, are all but ignored.’ While some historians, the author graciously acknowledges, do ‘demonstrate a genius for bringing their subject alive’, they are, he claims, either not in academic posts or ‘face brickbats and backbiting from their fellow professionals’. Military history, according to the author, is catered for entirely by non-academic historians. Academics he (an educated guess at the gender of the author) argues ‘need to escape from their intellectual caves and start paying more attention to big subjects such as the history of politics, power and nation-states.’

Now, I make no claims to having a genius for bringing my subject to life but, like all my colleagues doing our best to work with the current impact agenda, I am fully aware of the dangers of ‘learning more and more about less and less, producing narrow PhDs and turning them into monographs and academic articles, in the hamster-wheel pursuit of tenure and promotion.’ I don’t want to speak only to other historians, which is precisely why I jumped at the chance to appear on a nationally broadcast, BAFTA-winning programme which, for the first time in its history, was touching on a subject about which I had written a book. I hope and believe that my enthusiasm for the subject and the relevance of the type of document I was exploring with Dan came across, even if there wasn’t time or space for our discussion of the references to the Easter Uprising that occur in one letter, or the contemporary political significance of separation allowances as a form of proto-welfare benefit. Similarly, I hope and believe that the public lectures I gave on the ranks and work of RAMC throughout the First World War centenary and the variety of resources I helped produce for schools on the medical history of the war helped to both nurture public interest in history as a subject and inform debate over the relevance of the past to the social challenges of the present.

The problem isn’t that academic historians don’t do public history. We do, in far more ways than publishing books or appearing on television, as I have noted previously. Nor is it that we ignore war, politics or power structures by focusing on ‘marginal’ subjects. Social and cultural histories simply provide another way of looking at war, politics, economics, diplomacy. Indeed, the interrogation power structures are their very fabric, not their antithesis. I would strongly recommend Dr Daniel Todman’s (QMUL) acclaimed two-volume social history of the Second World War to Bagehot’s attention to see what I mean.

Rather, the problem is that public history is a different discipline from academic history. Doing both well is possible for a single individual, but it is hard and time-consuming, especially when added to the other expectations of teaching, administration, pastoral care and grant capture that are expected of academics today. I am becoming increasingly aware of just how different and difficult a discipline it is as I work to turn my academic research into a ‘trade’ book for wider public consumption (although even in its academic form it is free of charge to download, and I have been honoured to have it recommended as a useful resource for GCSE teacing). Even if I succeed in doing so, I doubt that the ultimate product will have anything like the breadth of impact that 5 minutes of speaking with the man who played Harry Potter about some of the work I did for my PhD and turned into an academic monograph has had. But that isn’t going to stop me trying because I am historian, even if one who happens to work in an academic job. And I believe from my experience in engaging with the public that people are interested in listening to these stories of those on the margins, including those on the margins in wartime, and hearing what they have to say about the world they lived in and how it shaped the world in which we live in today, even if Bagehot does not.