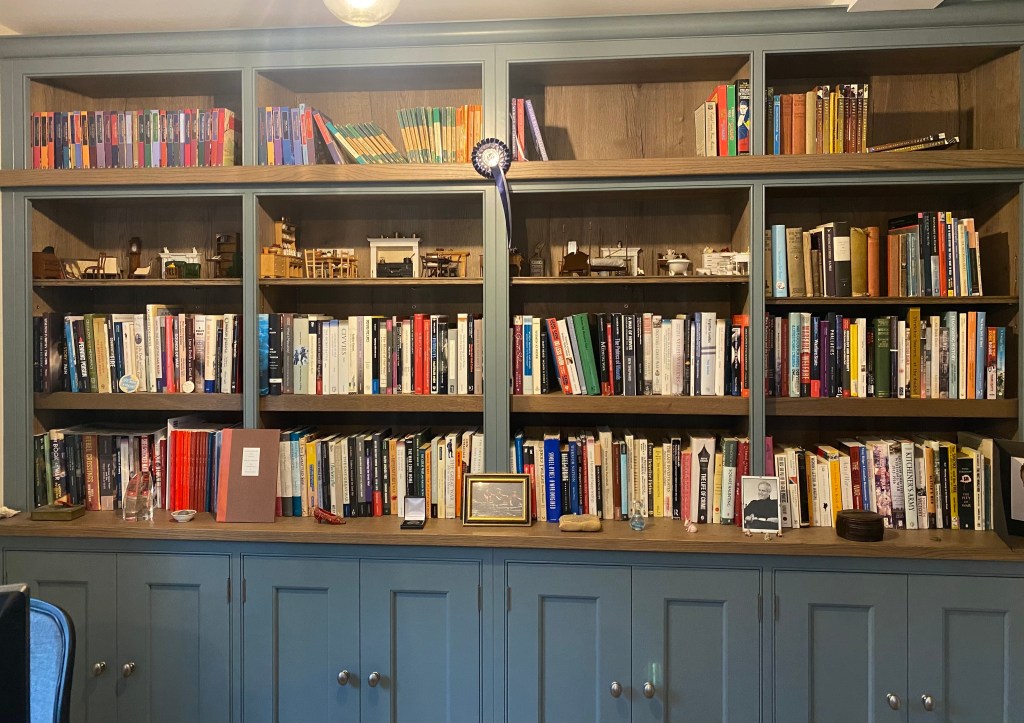

It has taken a week, but I have finally unpacked all the boxes of books and papers and accumulated office accessories that I acquired over 15 years at Leeds. So now that I am fully installed in my home office, it seemed like a good time to enumerate the projects I have underway and planned, and what I hope to acheive in the next 18 months.

Men of War: A Modern History

Under contract with Polity Press, with the manuscript due in 2028, I currently have aproximately 10,000 words of a very, very messy draft of Chapter One and a detailed outline of all eight chapters. The goal is to have a completed first draft by the end of the calendar year. I anticipate this being a complete mess, with the aim of a serious edit the following year.

The Return of the Soldier: British First World War Veterans and the Making of Twentieth Century Britain

This one is now on is fourth or possibly fifth subtitle as my ideas have shifted through the drafting process. I currently have between 3,000 and 5,000 words drafted for three of the five chapters, with a plan for a conference paper for the fourth chapter in the works. These will then form the cores around which I will build the longer chapter, with a full draft of ‘Return Home’ next on the agenda so that I can send it out to publishers and agents for consideration. The goal is to have a contract for this one by the end of the year.

The Return of the Soldier: British First World War Ex-Servicemen and the Making of the Twentieth Century

This project is now on its fourth or fifth subtitle, but, after far too long, I think I finally have a central thesis and a sense of the voice for this book. I also have 3,000 to 5,000 words for three of the five body chapters, with plans for a conference paper that will give me another 3,000 words for the fourth. These will go on to form the cores of the longer chapters. What I don’t currently have is a publisher so, in addition to the conference paper, my next step will be to write up the chapter on ‘Returning Home’ for submission to publishers and agents. The goal is to have a contract for this book by the end of the year.

A chapter on the ethics of doing disability history, accepted subject to minor ammendments.

This is due in two weeks, so is currently at the top of my priority list.

An 8,000-10,000 word chapter on front-line battlefield medical care.

I still need to check with the editor what the temporal and geographic scope of the expected chapter is. Submission in June.

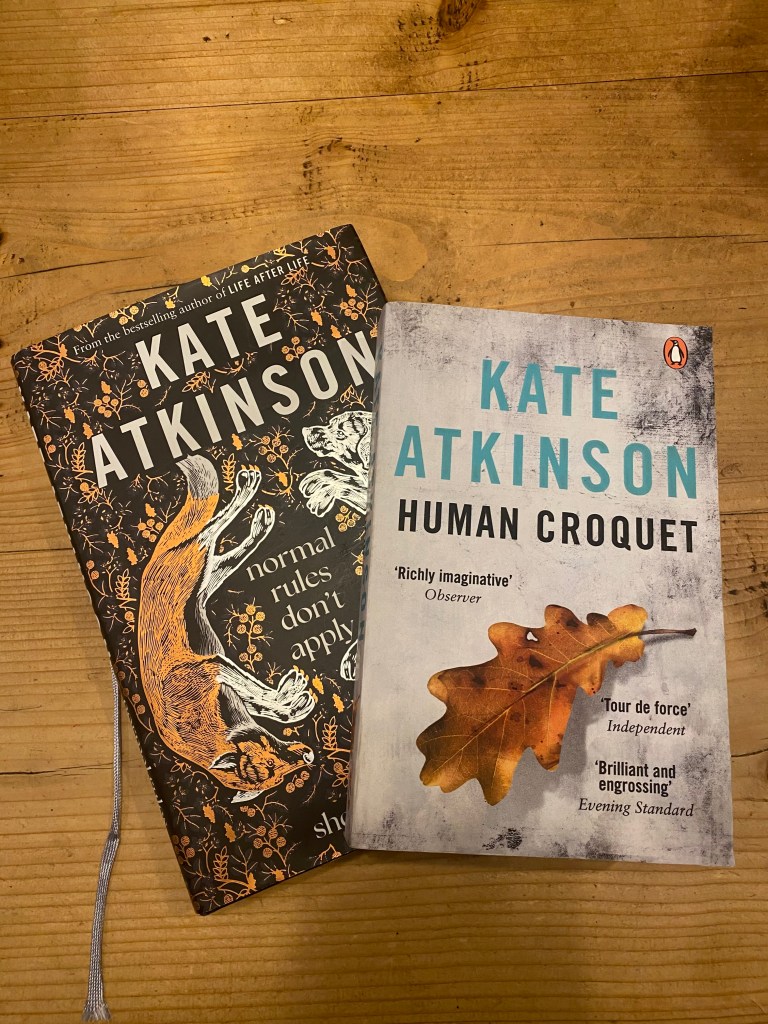

A history of Golden Age detective fiction and the two world wars.

I can’t really let myself commit to this one until I have the two on-going book projects much nearer completion, but I do want to get a proper proposal off to an agent. This is the one that has the most potential as a trade history, I think. Certainly, everyone I have mentioned it to has been very enthusiastic and encouraging. In the grand tradition of writing procrastination, this is, of course, the book I want to write at the moment.

The novel

I keep telling myself that this one is just for fun, that I have to prioritise the non-fiction because that is my bread-and-butter and where I am more likely to publish successfully. Really, I need to stop researching this one and just get on with writing it.

This blog

I am hoping to post on here once a week, but I am also aware that doing so risks taking writing time away from other projects. Indeed, this post has taken two days to write in what is an exceptionally busy week of family responsibilities and pre-existing commitments. So while a weekly post will be my goal, I will need to reassess this if either of the book projects start to suffer. In which spirit, I had better stop writing about writing, and get on with actually completing that chapter on ethics!

On the theory that

On the theory that